Apple Stories Part 3: Thomas Andrew Knight (1759-1838) - the RHS, pineapples, and the 'Pomona Herefordiensis'

- gardenhistorygirl

- Dec 12, 2025

- 28 min read

Updated: Dec 14, 2025

'The Downton Pippin', Plate 9. From 'Pomona Herefordiensis', Thomas Andrew Knight,1811. Knight noted that the drawing was perfectly accurate as it was a portrait of “branches selected by myself from young trees in my nursery”

Introduction

Back in the autumn of 2023, I visited Croft Castle, a National Trust property close to where I live in Herefordshire, to see an exhibition celebrating the cultural significance of the apple to the county’s history. That visit inspired the first two parts of my ‘Apple Stories’: the first about The Herefordshire Pomona (an ‘apple book’, published in parts between 1878 and 1884) and the second, The National Apple Congress of 1883 (a kind of census of apples grown in the UK held by the Royal Horticultural Society with a view to organising their nomenclature).

Portrait of Thomas Andrew Knight by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1794

This, the third part of my Apple Stories again refers back to the Croft Castle exhibition and another local, Herefordshire, connection. This time it concerns an earlier ‘apple book’, Pomona Herefordiensis, compiled and edited by Thomas Andrew Knight and published in 1811 – which was also on show at Croft Castle's exhibition.

For this post, I'd intended to concentrate on Knight and his Pomona Herefordiensis, but it turns out that he was also instrumental in the early days of the Horticultural Society of London formed in 1804 – later renamed the Royal Horticultural Society when it received royal patronage from Prince Albert in 1864 ('Horticultural Society'). Knight also became well known for successfully growing pineapples in his state-of-the art curvilinear glasshouse on his estate at Downton Castle. And as I can't resist such garden history 'rabbit holes', I've changed the title of my post accordingly to include those aspects of his life.

I've also peppered this post with botanical illustrations by William Hooker (1779-1832) of fruits raised by Knight. Hooker not only produced illustrations for Knight's Pomona Herefordiensis, but also became well-known for his drawings and engravings of plants for the Transactions of the Horticultural Society (often accompanying papers written by Knight) and the Pomological Magazine [see Note 1]. [This William Hooker not to be confused with William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), who, in 1841, became the first Director of Kew.]

‘Mr Knight’s new Peach from an Almond’, Plate 1 by William Hooker. From ‘Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London’, Vol. 3, 1822

Thomas Andrew Knight (1759-1838)

Knight is mostly well-known as a British horticulturist and botanist, who served as second President of the Horticultural Society for many years (1811-1838). However, it's his elder brother, Richard Payne Knight (1751-1824), who is much better known to garden history for his theories on the ‘picturesque’ [an aesthetic concept of late 18th century Britain] – his most influential book being An Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste published in 1805, which discussed ideas of ‘taste’ and the concept of the ‘picturesque’ following on from the writings of William Gilpin and Uvedale Price.

The brothers mostly lived at Downton Castle (their grandfather's estate), just a few miles from Croft Castle, to which they had a family connection as it was owned by their uncle, Richard Knight (1693-1765). Thomas was heir to his unmarried elder brother, who, in turn, had been the heir of their father and also their uncle. And, in 1808, Richard Payne Knight, who seems to have preferred a ‘London life’, relinquished Downton Castle and the running of the family estate to his brother, moving to a cottage on the estate.

Watercolour titled ‘The River Teme at Downton, Herefordshire’ by Thomas Hearne, 1785-1786

Richard Payne Knight employed artist Thomas Hearne [(1744-1817) a English landscape painter, engraver and illustrator to draw several views of the grounds of Downton Castle, including this one – an example of the ‘picturesque’ style with its river, rocks, winding path and rustic bridge supported by tree trunks.

Thomas Andrew Knight was born in 1759 at Wormsley Grange, a few miles from Hereford. The youngest son of the Rev. Thomas Knight, it was assumed that following his graduation from Oxford he would follow his father into the church. After leaving Oxford however, he instead returned to Herefordshire and took up life as a country gentleman.

'Wormsley Grange, Herefordshire'. From 'The Herefordshire Pomona', Vol. 1,1876-1885 [This 'apple book' was published several decades after Knight's Pomona Herefordiensis.]

Knight's interest in fruit, cider apples in particular, may have begun when, according to one source [see Note 2], Knight did some work surveying Herefordshire for the then government, and found that the county’s orchards were in a severe state of neglect. Other sources say that after Oxford he 'studied horticulture', but I rather think it was probably a case of self-study rather than anything more formal. However, it's generally agreed that by the late 1700's, Knight was using a large part of his inheritance (of both land and wealth) to research and develop disease-resistant cultivars of fruit trees which he bred and planted in their thousands at Downton Castle.

'Portrait of Thomas Andrew Knight holding an oak branch' dated January 1837, by Edmund Ward Gill. Courtesy Hereford Museum and Art Gallery

Knight’s subsequent publications, and practical experiments, all being part of his attempts to improve cider orchards – with one source asserting [Note 2 again] that his efforts helped to increase the interest in cider, with many cider orchards being restored “and small-scale cider making revived”.

His most famous varieties of cider apples were the 'Downton Pippin', as shown at the top of this post [in the entry for this apple in the Pomona Herefordiensis, Knight notes that the original Downton Pippin tree grew at Wormsley Grange] – and 'Knight’s Seedling' [strangely, I've found nothing further on this particular apple, nor any image of it].

Like many other wealthy gentlemen of the time, Knight became a fellow of the Royal Society (1805) and a fellow of the Linnaean Society (1807). He contributed 46 papers to Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society, over 100 to the Transactions of the Horticultural Society, as well as a Treatise on the Culture of the Apple and Pear, and on the Manufacture of Cider and Perry in 1797, and, most famously, the Pomona Herefordiensis in 1811. A selection of his papers, together with a biographical sketch of Knight’s life, were published in 1838.

The list of Knight's works, below, shows the breadth of his horticultural interests and research. Many of them contain his comments about particular fruits, so I often quote from them in this post – full details in the [copious!] Notes at the end of this post.

Extract from John Claudius Loudon’s 'Encyclopedia of Gardening', 3rd edition, 1825, titled 'British Works on Gardening' which lists Knight's written works – mostly papers published in the Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London

As can be seen from the above list, Knight’s plant breeding efforts also included other crop plants such as peas, strawberries, potatoes, plums and nectarines. Many are named after him or his various estates, including two types of cherries – The Downton Cherry and Knight's Early Black Cherry, both described, and illustrated by Hooker, in the Pomological Magazine in 1830 and 1834 respectively. While the Downton Strawberry, shown below, raised at Downton Castle by Knight from seed, featured in a paper read to the Horticultural Society in 1819 [see Note 3].

‘The Downton Strawberry’, Plate 15, by William Hooker. From ‘Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London’, Vol. 3, 1822

By 1827, the Wormsley Grange estate is said to have had 18 orchards which Knight improved by paying for new trees, rather than undertaking any of the work himself. An earlier account, in 1821 [quoted in Geography and Enlightenment, published by the University of Chicago (1999)], provides a little more detail and indicates that 331 apple and pear trees were “freshly planted at Knight’s request” [see Note 4].

Today, Knight's birthplace, Wormsley Grange, and its surrounding farm are used as holiday accommodation. Its website [see Note 5] nicely acknowledges its history with the Knight family – and all 12 bedrooms are named for apple or pear varieties in recognition of Knight's work. Many of his earliest experiments with grafting apple and pear trees were probably carried out in its orchards. Both Thomas and his brother, Richard Payne Knight, are buried in Wormsley churchyard.

Photograph courtesy Wormsley Grange

In 1811, Knight’s paper about "some Pears and Apples" [see Note 6], described the Downton Pippin as equally well suited “for the dessert, the press, and for every culinary purpose”, and the Wormsley Pippin, shown below, which ripens at the end of October, as being simply “the best Apple of its season”.

'The Wormsley Pippin Apple', Plate 80 by William Hooker. From 'The Pomological Magazine', Vol. 2, 1829

Knight and the [Royal] Horticultural Society

It was Knight’s friend, Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, who nominated him as a founder member of the new Horticultural Society – writing to him in March 1804 that he had taken “the liberty of naming you as an original member”. Knight replied, accepting the nomination with “great pleasure”, adding that he had “long thought that such a Society might be productive…”.

As Murray Mylechreest writes in his article 'Thomas Andrew Knight and the Founding of the Royal Horticultural Society' for Garden History [the journal of the Gardens Trust, see Note 7], just a year later, Knight was invited to write a Prospectus [what we’d probably now call a Mission Statement] for the new Society. His subsequent paper, titled Introductory Remarks relative to the Objects which the Horticultural Society have in view, was read to Society members in April 1805 by Banks, and subsequently published in the Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London, Vol.1, 1820.

In his Remarks, Knight wrote that the Royal and Linnean Societies, as well as various agricultural societies, had generally neglected the subject of horticulture – and “the establishment of a national society for the improvement of Horticulture has therefore long been wanted”. Adding that horticulture “in its present state” concerned “the useful” and “the ornamental”, he thought that the first would mostly occupy members of the Society, although the second would not be neglected. Perhaps, not surprisingly, his remarks focus on the culture of various species of fruit. His comments generally lament the quality of much of horticulture – seeing much room for improvement. He ends his Remarks by saying that, in order to improve “practical horticulture”, the Society hoped to “receive the support and assistance of those who are interested in, and capable of promoting, the success of their endeavours”.

'The Foxley Apple, Plate 14. From 'Pomona Herefordiensis', Thomas Andrew Knight,1811.

This small crab apple was created by Knight at his nursery at Wormsley Grange and named after the estate of his friend, Uvedale Price

Today, we're used to the, now named, Royal Horticultural Society, being a horticultural organisation interested in all aspects of gardening. However, when it was first established, its first major challenge was to record, name and identify the vast number of UK apples and pears. As the RHS points out today [see Note 8], at the time this was particularly important for the horticultural trade – from market gardeners and amateur gardeners, to the cider and perry producing industries.

Therefore, the initial objects of the Society concentrated on improvements in fruit cultivation and, as a review of the Prospectus published in the British Critic indicated [a review magazine, Vol.25, 1805 quoted in Mylechreest's article], Knight's hope was fulfilled in that the Society was indeed “composed of names so distinguished for their talents, and of such elevated character in life, that much advantage must necessarily arise from its exertions”.

A Silver Knightian Medal, depicting Thomas Andrew Knight's portrait, from 1836. Courtesy RHS Lindley Collections

Knight’s influence on the Society lasted until his death – with his long term achievement being to establish, as Mylechreest notes, “a Society having a scientific outlook in bringing about horticultural advances”.

Today, we all know of the gold, silver, silver-gilt and bronze medals –- albeit on a piece of fancy card, that the RHS awards at their flower shows. However, in the past, they issued actual medals, named for early officers of the Society, such as Joseph Banks [Banksian medal] – and, of course, for its long-term President, Thomas Andrew Knight. The medal shown here was, fittingly, awarded in 1912 to a Mrs Gordon Channing for apples and pears. Other early examples below from The Gardeners' Chronicle.

The Gardeners’ Chronicle, June 19, 1841

Pineapples – and Knight's Curvilinear Glasshouse

Knight was also famed for his experiments with growing pineapples – the 'must have' tropical fruit of the day. First grown in the UK in the early 1700's, during the Georgian and into the Victorian period, the pineapple was seen as a symbol of wealth and status for their owners as it was rare and difficult to grow in colder European climates. It was also a testament to a gardener's skill in raising the plants to fruiting. Traditionally grown using 'bottom-heat' in pits produced by horse manure and tanner’s bark, Knight experimented with just using the heat generated by a glasshouse in the summer months, with the addition of a single fire to also heat the air.

'The Black Jamaica Pine', watercolour by William Hooker. From 'Hooker’s Fruits', Vol.1, plate 19, 1815 (RHS Digital Collections). Public Domain

Published in 1822, the unnamed author of a book titled The Different Modes of Cultivating the Pine-Apple [see Note 9] begins the Introduction with reference to Knight’s experiments in cultivating pineapples, writing that “A considerable interest has been excited in the Horticultural world” by those experiments. The book describes Knight’s methods, and quotes extensively from his paper published in the Transactions of the Horticultural Society in 1819.

Knight writes about his ideas for growing pineapples in a chapter in this book but as his hot-house (which he describes as 40ft long by 12ft wide) did not have the benefit of the latest glasshouse technology i.e. "a curved iron-roof such as those erected by Mr. Loudon” [see Note 9 again], he deferred purchasing plants until the following spring (1819) when he hoped his new hot-house would be in place. Such a curvilinear roof would be superior, he wrote, and give such advantages as being cheaper to erect, more durable, require less expense in painting it, and admit much more light.

Title page of 'The Different Modes of Cultivating the Pine-Apple',1822

And here, some background to the importance of the development of curvilinear roofs. Famed horticultural writer, John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843), is recognised as the inventor of the wrought iron glazing bar in 1816 which strengthened glasshouse roofs. They were also more malleable, which allowed the bars to be welded together or bent to the desired curve or shape – thus the curvilinear roof.

As Edward Diestelkamp writes in an article about curvilinear roofs in the journal of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation [see Note 10], Loudon in particular promoted the concept of curvilinear glasshouses while encouraging improvements “in the creation of artificial climates and in the design and construction of hothouses, greenhouses and conservatories for producing domestic and exotic fruits and housing botanical specimens”. And in the early decades of the 19th century, as Dieselkamp points out, the Society “enabled the exchange and dissemination of ideas and theories on the optimum design of horticultural structures through lectures, discussions and the publication of illustrated papers by horticulturalists and gardeners”.

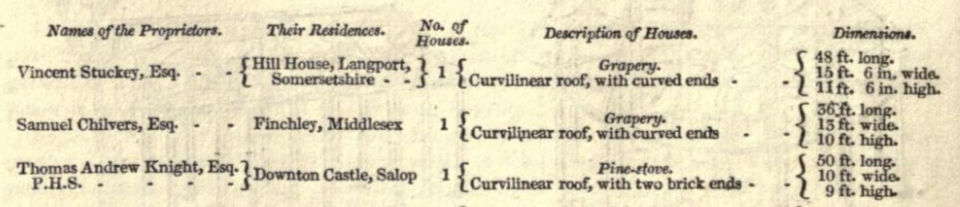

In another paper on the subject by Diestelkamp, this time for the 1987 Georgian Group Symposium [see Note 11], he writes that Loudon’s first glazing bars were produced by iron founders, W. and D. Bailey in London. As Loudon later wrote in the 3rd edition of his Encyclopedia of Gardening (1825), he transferred the rights for his invention to the company in 1818 in order “to render all these improvements" available to the public. Adding that they had, "from our plans, constructed in a most excellent style of workmanship, the curvilinear houses in different parts of the country…”. Loudon’s book even provided a list of “proprietors” and their “residences” where Bailey’s had erected curvilinear houses – including Knight at Downton Castle, described as a “Pine-stove” as shown below.

Extract from Loudon's 'Encyclopedia of Gardening', 3rd edition, 1825

However, it was not until June 1820 that Knight's curvilinear glasshouse was completed, and he then set about his experiments with 9 pineapple plants. His paper includes a picture of it – describing it as being “simple”, with the roof admitting “as much light as any roof that can be constructed in the present state of knowledge in the combination of wrought iron and common glass”. It was 50ft long and 10ft wide with a furnace at one end – with stepped staging for the pots of pineapples “so as to stand as near the glass as possible”.

Figure 18 from Knight's chapter titled ‘Of the improvements in the culture of the Pine Apple’ showing Knight’s curvilinear glasshouse. From the book 'Different Modes of Cultivating the Pine-Apple', 1822

Knight’s curvilinear 'pinery' still standing in the kitchen garden at Downton Castle, Herefordshire. Photograph by Edward Diestelkamp, courtesy Downton Castle. Historic England listed the glasshouse Grade II in 2000

Knight wrote (quoted in his Improvements chapter) that his new hot-house, with a back wall of 8ft 6” and a front wall of only 1ft 6”, could house some 200 fruiting pineapples. The temperature in the hot-house was kept to between 70-95 degrees Fahrenheit which led the plants, purchased in July, to show fruit and blossom by October.

And in his paper, read to the Horticultural Society in October 1822 ['Upon the Advantages and Disadvantages of curvilinear Iron Roofs to Hot-houses' see Note 12], Knight describes both the advantages, and disadvantages, of curvilinear iron roofs in hot-houses after some 3 years of his experiments growing pineapples. Using just a “single fire of moderate size” to heat the glasshouse, he was able to successfully grow the fruits “in all seasons of the year, without the aid of bark or hot-bed of any kind” [the usual method] – although he admits that while growing successfully, only a few ripened sufficiently to harvest. His paper also provides a very nice diagram of the “house”, shown below.

What Knight doesn't say is that to keep the glasshouse at an even temperature would have required great expense and constant attention. The fires in such glasshouses (before the advent of boilers) would need tending all day and all night – usually by a 'garden boy'.

Plate 8, 'Section of Mr. Knight’s curvilinear house', from his article ‘Upon the Advantages and Disadvantages of curvilinear Iron Roofs to Hot-houses. In a Letter to the Secretary. By Thomas Andrew Knight, Esq. F.R.S. President’. From 'Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London', Vol.5, 1824

And for anyone interested in the detail, here's a list of the References in Plate 8.

According to Diestelkamp, the pinery at Downton Castle is the earliest surviving example of such a roof – designed by Knight, reflecting “his thoughts on the optimum shape for a hothouse or greenhouse”, as outlined in papers he wrote for the Horticultural Society in 1817 and 1824 [see Note 13].

And here, just a brief explanation of the term pinery. According to garden historian Michael Symes’ A Glossary of Garden History Terms (my edition 2000), a pinery “is a greenhouse for the cultivation of pineapples; or a wood of pine-trees”. For a bit more detail, it’s a specialised glasshouse, usually south-facing and designed to maximize both heat and light for the growing of pineapples in colder climates.

Knight and the Lost Gardens of Heligan

Knight also has a connection to the Lost Gardens of Heligan with regard to pineapples. When Tim Smit and John Nelson began the garden’s restoration in the late 1990’s, the remains of Heligan’s pineapple pit, thought to date from 1840-50, most closely resembled the kind of pits described by Knight in his article, ‘Description of a Melon and Pine Pit’, read to the Horticultural Society in 1822, and then published in their Transactions in 1824 – this type of pit using the usual ‘bottom heat’, i.e. dung, rather than growing in glasshouses. This is detailed in an article published in Sibbaldia: The International Journal of Botanic Garden Horticulture in 2008 ['Pineapple Growing: Its Historical Development and the Cultivation of the Victorian Pineapple Pit at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, Cornwall’ by Johanna Lausen-Higgins and Phil Lusby]. However, I'm not going into any more detail on this here – as it's yet another rabbit hole..., and I'll be writing about the Pineapple in the future.

Pomona Herefordiensis

'A Treatise on the Culture of the Apple & Pear and on the Manufacture of Cider & Perry' by Thomas Payne Knight, 1797

Knight had already produced three (unillustrated) editions of his Treatise on the Culture of the Apple and Pear and on the Manufacture of Cider & Perry [published 1797, 1802 and 1809], before publishing the Pomona in 1811. Two more editions of his Treatise followed in 1813 and 1818.

Brent Elliott of the RHS Lindley Library, writing about English fruit illustration in the early 19th century [see Note 14], points out that the illustration of fruit cultivars had been, since the early 17th century, a "special category of plant portraiture", and one which produced several important works. Knight's Pomona being one of them.

Published in parts between 1808 and 1811 at 8 shillings each at two monthly intervals, each part featured 3 beautiful coloured plates describing apple or pear varieties – and as usual for the time, each fruit was depicted attached to a branch, accompanied by some of the leaves. The price for the entire work, with coloured plates, was 6 guineas, or 4 guineas for an uncoloured version. Knight’s introduction – or Preliminary Observations, runs to 8 pages, followed by the plates each accompanied by text describing the cultivar shown. In total there are 24 plates of apples and 6 of pears.

'The Red Must', Plate 4. From 'Pomona Herefordiensis', Thomas Andrew Knight, 1811

Most of the apples and pears in the book were long-established varieties, although as Elliott points out, 3, or perhaps even 4, were actually raised by Knight himself: Grange, Downton (named after the Knights’ estate), Foxley [see above], and possibly, Siberian Harvey.

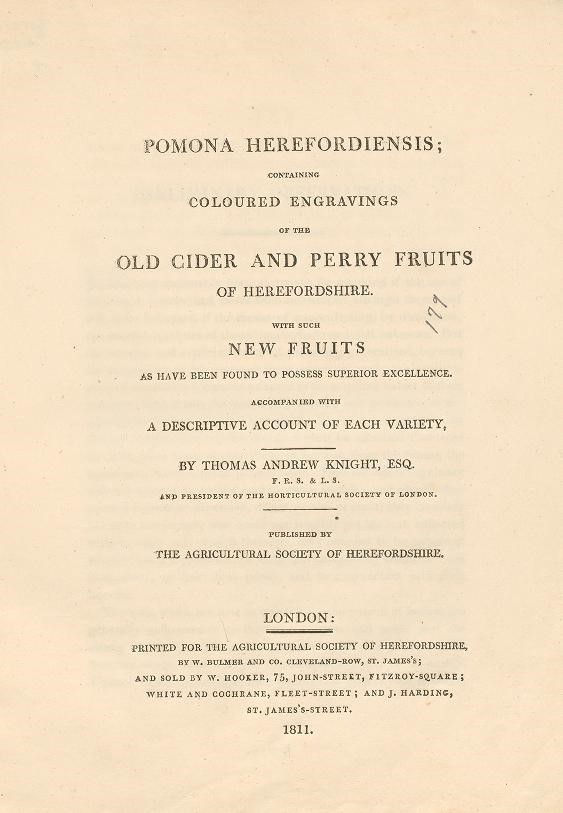

Title page from 'Pomona Herefordiensis' by Thomas Andrew Knight, Esq., F.R.S. and L.S. and President of the Horticultural Society of London, 1811

The Lindley Library’s copy of Knight’s Pomona usefully includes a ‘prospectus’ for the book describing its ambition to prevent “the losses and inconveniences” from the “rapid decay of every old variety of the apple and pear” – and that the Agricultural Society of Herefordshire [of which Knight was a founding member] had proposed the publication of “coloured plates of those old varieties to which their county has been indebted for its fame…”. The prospectus also pointed out that, while written descriptions alone had proved sufficient for botanists to distinguish one species of apple or pear from another, coloured plates allowed “those slight discriminations of character, which often distinguish one variety of fruit from another, of any given species”.

The later Herefordshire Pomona mentioned in my Introduction (published in parts between 1878 and 1884), includes a whole chapter (by its co-author, Dr. Henry Graves Bull) on Knight titled ‘Thomas Andrew Knight and his Work in the Orchard’ – so it’s an interesting look back to his work from the creator of another Pomona some 70 years later. Bull describes him as being “the best practical gardener of his time” in relation to his work introducing new varieties of fruits and vegetables “by means of hybridization”.

Knight's 'Pomona Herefordiensis' on show at Croft Castle. My photo September 2023

One interesting inclusion in this chapter is a table [below] showing what Bull describes as Knight’s “chief experiments in crossing apple trees…“ . Bull seems more certain about the creation of the Siberian Harvey apple than Elliott.

Table showing Knight’s “chief experiments in crossing apple trees” from ‘Thomas Andrew Knight and his Work in the Orchard’ by Dr. Henry Bull. From 'The Herefordshire Pomona', Vol.1, 1876-1885

'The Siberian Harvey', Plate 23. From 'Pomona Herefordiensis', Thomas Andrew Knight, 1811. [In the accompanying text, Knight notes that the original tree produced its first blossoms in 1807, and as the drawing was done in the “cold and wet season of 1809”, the fruit were somewhat smaller than usual]

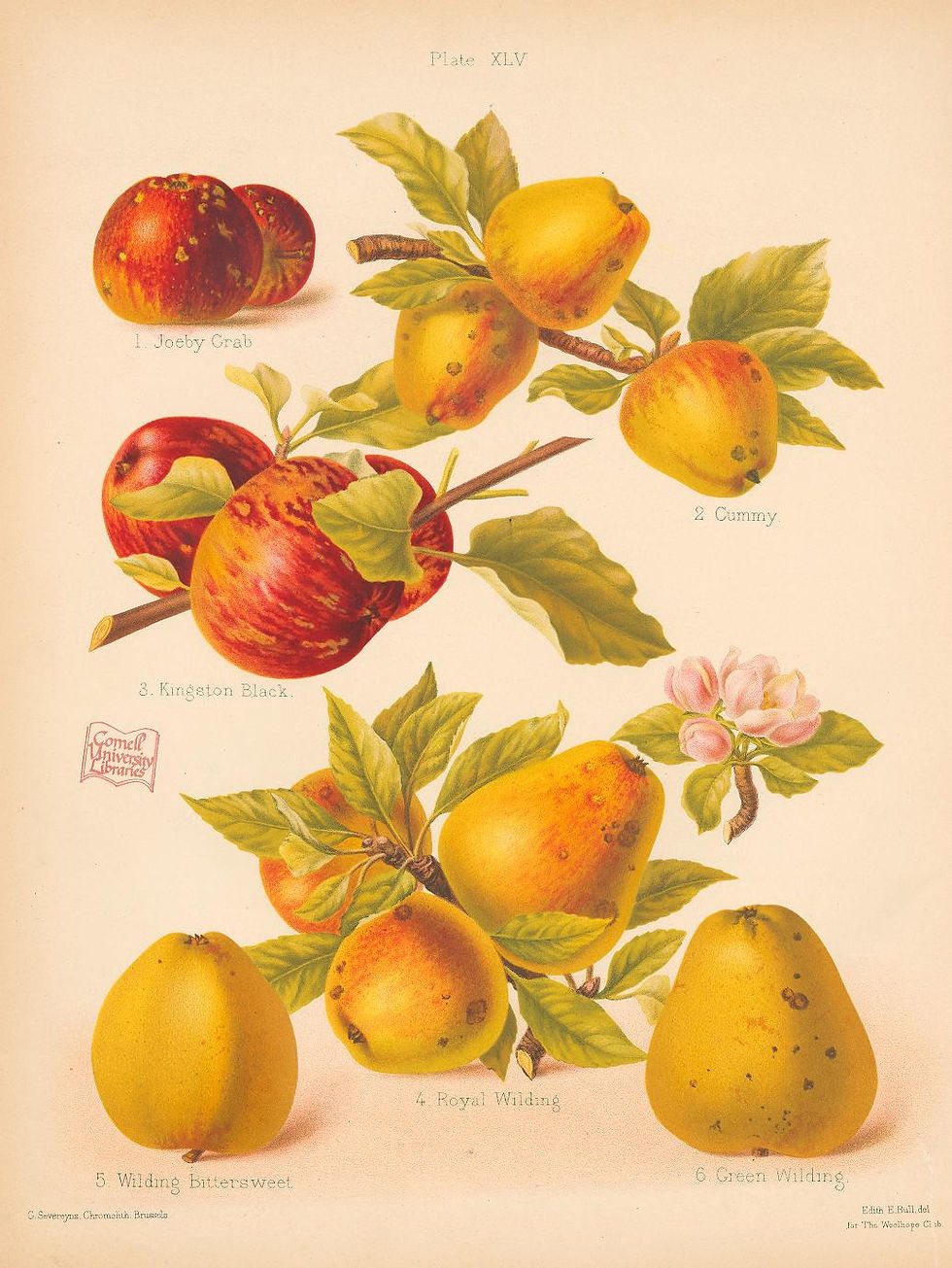

The Illustrations

The original drawings for the Pomona Herefordiensis were made by artists Elizabeth Mathews (1781-1860) and Frances Knight (1794-1881, Thomas Knight’s daughter – later Mrs Frances Stackhouse Acton. While William Hooker [an English student of famed German botanical illustrator Franz Bauer], created the etchings that, according to the author of Cornell University Library's online exhibition of the Pomona, “brought these drawings to brilliantly hued life”. And, just like the later Herefordshire Pomona several decades later, the artists took care to include life-like representations of the “blemishes observed on gathered specimens” including “scabs and speckles” [see Note 15].

There is plenty of information available regarding Hooker [as already mentioned, not to be confused with William Jackson Hooker of Kew fame – and no relation] so, briefly he was a well-thought of botanical illustrator, Elliott describing him as "probably the most eminent painter of fruit in 19th century England" [see Note 16]. He became the official artist of the Horticultural Society in around 1812 until his retirement in 1820, and was commissioned by them to visually, and accurately, record various fruits for a major fruit identification study they undertook. Each year around 25 watercolour drawings were produced and bound into volumes, eventually totalling some 250 paintings contained in 10 volumes. Following on from his excellent work producing etchings for the Pomona's plates from the drawings of Elizabeth and Frances, Hooker must have been an ideal candidate for the Society.

Elliott also points out that, in 1814, the Horticultural Society formed a committee to supervise the programme of fruit drawings by Hooker which, not surprisingly, included Knight (being the Society's President).

Elizabeth Mathews (1781-1860) [sometimes spelt Matthews]

Brent Elliott identifies Elizabeth as one of 6 daughters of a John Matthews of Belmont in Herefordshire, and that she was “obviously a talented artist”. However, he writes that only the first plate in the Pomona bears Elizabeth’s signature – “Elizth Matthews delt”. The only additional information I’ve found is through her parents. Her father's title was Colonel Dr. John Matthews, as he was a physician, and a Colonel in the local Herefordshire militia, while his wife, Elizabeth Ellis (1757-1823), was a miniature painter. The only image I’ve found of Elizabeth, our Pomona artist, is the one below painted in the early 1800's. In Knight’s ‘Preliminary Observations’ at the beginning of the Pomona, he only writes briefly about the two women, writing of Elizabeth that she executed all but three of the drawings for the Pomona, as they lost, “through ill health, the skill and talents of Miss Mathews of Belmont”.

'The Misses Matthews', watercolour on paper by Samuel Shelley, c.1800-1810. Courtesy National Trust Collections. [Elizabeth, our Pomona artist, is seated in the middle.]

And here I found another garden history 'rabbit hole'! Elizabeth Ellis was an heiress which allowed John Mathews, following their marriage to build a new house, Belmont House, a few miles from Hereford, work beginning in 1788. Mathews apparently consulted Humphry Repton regarding the design of the park, which overlooked the River Wye, although according to an article in Garden History in 1994 [see Note 17], the extent of Repton’s involvement at Mathews’ estate had not yet “been fully established”, particularly as it was not documented by a Red Book [although Repton's work in Herefordshire was quite early on in his career]. A more up-to-date report, albeit in 2010, for Herefordshire Council [see Note 18] describes the landscaping, under the title ‘Unregistered Historic Park and Gardens’ only as “advised by” Repton.

Frances Stackhouse Acton - nee Knight (1794-1881)

'Portrait of Frances Stackhouse Acton'. Date unknown. From a private collection, courtesy Acton Scott Working Farm Guide Book

To my delight, there's rather more information about Knight's daughter, Frances, even though, in the Pomona's introduction, he writes that the 3 plates that Elizabeth was unable to execute were undertaken by the ”work of a very young and inferior artist of my own family [i.e. Frances]; but those were finished under my own eye, and were most perfectly correct…”.

A little harsh perhaps [and Frances was, in later life, noted for her watercolours] , but Knight seems not to have been a distant Victorian father; he actively engaged with his children and, according to several sources [including a 1999 University of Chicago book, Geography and Enlightenment see Note 19], it was Frances who wrote the biographical sketch, 'Life of Thomas Andrew Knight, Esq.' which was included with a selection of his papers [see Note 20] published 3 years after his death.

The delay was, according to its 'Introduction', because “the gentleman” who had undertaken to write the memoir had to withdraw due to ill health and it had, therefore, been written by “those unused to write for the public eye, and whose judgment may probably be biassed by the devoted respect and affection they feel for the memory of the beloved parent…”. Knight's entry in The Dictionary of National Biography, [see Note 21] while noting that the volume of his papers was edited by George Bentham and John Lindley, also presumes that the 'Life' [as its usually referred to] was written by Frances.

There's also a more contemporary source – although at a distance of some decades. In the later Herefordshire Pomona, Dr. Henry Bull, the editor, also writes in the General Introduction that it was Frances who provided much of the information for it.

The 3 plates drawn by Frances Knight were of Stead’s Kernel, the Old Pearmain, and the Friar, as seen here. 'The Friar', Plate 30, from the 'Pomona Herefordiensis'

The 'Life' does indeed contain some insight into Knight's relationship with his children and, in particular, with Frances. For example, when Knight’s children were young he was “anxious to cultivate in them a taste for horticulture, natural history, and other rational pursuits”. He was “always ready to lay aside his book to answer their questions or to assist in their amusements” – his daughters spending many happy hours with their father in his study or in his garden.

At 18, Frances married an older land owner, Thomas Pendarves Stackhouse, who was 43 at the time. After he died (and they having no children), she was able to pursue her own interests – primarily archaeology and architecture. Fortunately, Frances went on to greater things and even [hurrah!] has her own Wikipedia entry under her married name of Frances Stackhouse Acton – so please do look her up.

But that's not the end of it with regard to Frances and, in a way, brings my Apple Stories full circle.

Some 70 years after the publication of her father's Pomona Herefordiensis in 1811, she made a drawing for Bull's Herefordshire Pomona in 1878 [just 3 years before her death] – Bull writing that it was, for Frances, "a source of great pleasure" to do so. Her drawing of the Eggleton Styre apple can be seen in the plate below.

Plate XXIX from 'The Herefordshire Pomona', Vol.1, 1876-1885 showing (top right) Frances’ drawing of the Eggleton Styre cider apple

Acknowledgement of Frances' drawing, bottom right in plate above

Frances died in January 1881 at the age of 87 and, one month later, an obituary appeared in The Gardeners’ Chronicle [see Note 22], which described her as “an accomplished artist and authoress” with “a wide knowledge of geological, botanical, horticultural, and antiquarian lore” having been, before her marriage, her father’s “constant associate in the many experiments carried out at Downton Castle which gave such an impetus to scientific horticulture in the first quarter of the present century”.

'The Acton Scott Peach' by William Hooker. From 'Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London', Vol. 2, 1822. [A new peach raised by Knight c.1815, and named for the estate of his daughter Frances’ husband.]

What of the gardens at Downton Castle?

During Knight's time at Downton, it seems they were functional rather than ornamental, as described by Loudon in his Encyclopedia of Gardening, 3rd edition of 1825. Despite describing Knight as “the first of all horticultural connoisseurs”, Loudon writes of Downton as being an "experimental ground" of several acres, with "various hot-houses, pits, and frames" – better considered as "horticultural workshops" where "beauty and order is not to be looked for". Knight also, by his own admission [writing in Transactions], only employed garden labourers acting under his supervision, rather than professional, or even, a Head Gardener.

Although the 'park and garden' at Downton are Grade II listed, a formal garden and pleasure grounds were not added, according to its Historic England entry of 1998/99 [Downton Castle, Burrington - 1000497 | Historic England] until later in the 19th century, well after Knight's death. Although some of the picturesque landscaping on the estate undertaken by his brother, Richard Payne Knight, does survive.

'Downton Castle, Herefordshire'. Engraved by H.W. Bond after J.P. Neale, 1831 [Note the gardener rolling the path.]

There are two contemporary reports on the gardens at Downton. The first, in The Gardener’s Magazine published in May 1838 (the month and year of Knight’s death), relates to a visit the previous September. The unknown author of the report describes the scenery of the estate as “eminently picturesque”, but writes that there are no ornamental grounds attached to the castle, only a lawn planted with a few shrubs. Knight’s primary concern was, he wrote (echoing Loudon’s remarks), the kitchen garden, where he carried out his “horticultural experiments”. The writer even points out that visitors, who have heard of Knight and his horticultural work, and who probably expected to find “a splendid place”, would generally be disappointed “at the first sight of Mr Knight’s garden”. However, he added, any gardener, would benefit “from an inspection of Downton Gardens, and a conversation with its benevolent and scientific owner”.

The report also mentions, not only the “curvilinear pine-houses”, but a melon house and fig house, while the kitchen garden contained a peach house. Interestingly, he also writes of Knight’s gardener, a Mr. Lander, describing his as “a most intelligent and obliging man”. So perhaps Knight had employed a more professional gardener as he aged.

A later report in The Gardeners’ Chronicle [June 14,1862], some 24 years after Knight’s death, describes a garden together with landscaping designed by famed landscape architect, William Andrews Nesfield [yet another rabbit hole, but this time I've avoided the temptation to pop down it!]. Many of Knight’s fruit trees were reportedly still growing in the kitchen garden, including a "fine old mulberry".

Today however, the Downton estate is private and not open to the public, and there's very little information regarding the gardens today.

In conclusion

Many sources describe how Knight intentionally shut himself off from the influences of outside scientific sources, although he corresponded with interested parties around the world, meeting some of them during his annual visits to London – no doubt attending meetings at the Horticultural Society. Despite this, as can be seen from his list of papers on various subjects, he was no slouch!

‘The Red Ingestrie’, Plate 17, engraved by S. Watts from a botanical illustration by C.M. Curtis. From the ‘Pomological Magazine’, Vol. 1, 1828. Raised by Knight from seed c.1800 and planted out at Wormsley Grange. [It's described in the magazine as an excellent table apple]

Knight's entry in parksandgardens.org points out that both his practical and published work “encouraged landowners, commercial nurserymen and gentlemen gardeners to adopt his findings and to plant new, vigorous varieties [of fruit] with great success“. Several sources describe him as probably the most innovative botanist of his era – despite his theories about the ‘degeneration’ of fruit trees over time being largely disproved in the modern era.

Knight was also held in high regard by his contemporaries with friends including [as well as Joseph Banks as we’ve already seen], John Lindley, and Sir Humphrey Davey who described him as “the celebrated Philosopher & horticulturalist to whom we owe so many important discoveries on the physiology of plants”. Even Charles Darwin, according to Knight's entry in parksandgardens.org, acknowledged Knight’s breeding experiments in The Origin of Species.

As well as all his other accomplishments, during his lifetime Knight was also a strong proponent of agricultural improvement, and campaigned for various national agricultural reforms to ease the plight of small farmers and agricultural labourers [see Note 23]. And, according to Apples&People.org.uk [details at end of this post], he corresponded “with horticulturalists around world, and sending plants to them, and was awarded with honorary memberships and medals from agricultural and horticultural societies across Europe and America, and in Russia and Australia“. He also helped “to establish the North American apple industry” by sending large numbers of ‘scions’ [cuttings] of his new fruit trees to the Massachusetts Agricultural Society. Dr. Bull gives more detail on these honours in his chapter on Knight in the later Herefordshire Pomona, as well as providing us with a descriptive paragraph on his work with fruit and vegetables – as shown below.

Excerpt from the chapter titled ‘Thomas Andrew Knight and his Work in the Orchard’ by Dr. Henry Bull. From 'The Herefordshire Pomona' ,1876-1885

As I wrote in the Introduction, the Pomona marked the first published documentation of England’s ‘cider apple and perry fruit’ varieties – and it still has relevance today. An online exhibition of the Pomona Herefordiensis by the Cornell University Library (2025) sums it up nicely – describing the Pomona as a “sumptuous classic of English pomology…" at a time “when English orchards abounded in a dazzling diversity of fruit”. Something that we have lost. And that the Pomona is a perfect example of when “intrepid naturalists of the day found powerful partnership with some of the world’s most talented illustrators”. Not only in an effort to assist with the science, but to inspire the interest of “a wider (ideally deep-pocketed) populace” in exploring both newly opened-up, far away exotic lands, but also “the orchard next door” [again, see Note 15].

It's also Cornell that points out that the Pomona, and other such ‘apple books’ are still used today to assist science. For example, a professor at Cornell’s School of Plant Science is exploring large numbers of apple genotypes, often from forgotten orchards of the past, for their potential use in modern-day cider production. When the identification of particular cultivars are questionable (due to both genetic and chemical analyses), such historic literature can assist [see Note 24 for further information on this].

Thomas Andrew Knight in later life, portrait by Solomon Cole, 1835. Courtesy Collection of the Herbarium, Library, Art & Archives, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

And it’s nice to know the story of apples continues – despite the lack of choice that we have in most of our shops.

As I was finishing this post, my November edition of Gardens Illustrated arrived in the post and contained an interesting short article. Due to the bumper crops of fruit trees in the UK this year, the RHS has experienced an “unexpected influx of submissions” to its Fruit Identification Service – the service being a perk of RHS membership. This September, the Service received queries regarding more than 500 “mystery” or unknown apple cultivars. And of the few examples listed as identified was an historic cider apple, the Golden Bittersweet, which gets a mention, not in Knight’s Pomona Herefordiensis, but the later Herefordshire Pomona. Sadly, there’s no image of it in the Pomona, just a mention in the ‘List of Other Cider Apples’ which were exhibited at the Hereford Apple Shows organised by the Woolhope Club between 1878 and 1883 [see my Apple Stores: Part 1]. Although not figured, the entry describes this large Devonshire apple as having “a good repute as a cider apple”.

If you're particularly interested in the continuing story of the apple, I recommend https://applesandpeople.org.uk/, their aim being to highlight "just how significant and iconic this humble fruit has become".

Notes:

1. Link to volumes of the Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/151339#page/1/mode/1up and the Pomological Magazine: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/71181#page/7/mode/1up

2. TeePee Cider blog – Cider Musings: Thomas Knight and the Pomona Herefordiensis

3. Joseph Sabine, ‘Account and Description of the Downton Strawberry: a new Variety raised by Thomas Andrew Knight, Esq. FRS. & President’. From Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London, Vol.3, 1822

4. Stephen Daniels, Susanne Seymour and Charles Watkins: chapter 12, ‘Enlightenment, Improvement and the Geographies of Horticulture in Later Georgian England’. From Geography and Enlightenment, edited by David N. Livingstone and Charles W.J. Withers, University of Chicago Press, December 1999 - quoting the Hereford County Record Office

6. Knight, 'A short Account of some Pears and Apples, of which Grafts were communicated to the Horticultural Society’. From Transactions, Vol.1, 1820

7. Murray Mylechreest, 'Thomas Andrew Knight and the Founding of the Royal Horticultural Society', Garden History, Vol.12, No.2 (Autumn,1984)

8. RHS Digital Collections: William Hooker’s Fruit Drawings RHS Digital Collections | View | William Hooker’s Fruit Drawings

9. ‘Of the improvements in the culture of the Pine Apple, proposed by T.A. Knight, Esq. FRS PHS of Downton Castle, Herefordshire’. From The Different Modes of Cultivating the Pine-Apple, from its First Introduction into Europe to the Late Improvements of T.A. Knight, Esq, by a Member of the Horticultural Society (London), 1822

10. Edward Diestelkamp, ‘The wrought-iron greenhouse at Felton Park’. From Context, the journal of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation, No. 177, September, 2023

11. Edward Diestelkamp, ‘Building Technology & Architecture 1790-1830’. From Late Georgian Classicism, report of the Georgian Group Symposium, 1987

12. Knight, 'Upon the Advantages and Disadvantages of curvilinear Iron Roofs to Hot-houses. In a Letter to the Secretary’. From Transactions, Vol.5, 1824

13. Knight, ‘Suggestions for the Improvement of Sir George Steuart MacKenzie’s Plan for Forcing Houses’. From Transactions, Vol.2, 1817. And ‘Upon the Advantages and Disadvantages of Curvilinear Iron Roofs to Hot Houses’. From Transactions, Vol.5, 1824

14. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library. Vol.4, October 2010, Robert Hogg's Fruit Manual, 150th anniversary issue. Article by Brent Elliott: English Fruit illustration in the early 19th century. Part 1: Knight and Ronalds

15. Cornell University Library Online Exhibition: Apples to Cider – Pomona Herefordiensis, 2025 https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/cider/feature/pomona-herefordiensis

16. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library 7, 2012. English fruit illustration in the early 19th century. Part 2: Hooker, Withers and the Horticultural Society by B. Elliott of the Lindley Library

17. Hazel Fryer, Garden History, Vol.22, No.2 The Picturesque (Winter, 1994), article ‘Humphry Repton’s Commissions in Herefordshire: Picturesque Landscape Aesthetics

18. ‘Study of Options. Environmental Assessment Report Hereford Relief Road’, by Amey for Hereford Council, August 2010

19. Chapter 12, ‘Enlightenment, Improvement and the Geographies of Horticulture in Later Georgian England’, by Stephen Daniels, Susanne Seymour and Charles Watkins. From Geography and Enlightenment, edited by David N. Livingstone and Charles W.J. Withers, University of Chicago Press, December 1999

20. 'A Selection from the Physiological and Horticultural Papers, published in the Transactions of the Royal and Horticultural Societies, by the Late Thomas Andrew Knight' – 'To which is prefixed A Sketch of His Life' published in 1841, some 3 years after his death

21. ‘Knight, Thomas Andrew’ by George Simonds Boulger, The Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 31.

22. ‘Obituary’, The Gardeners’ Chronicle, February 5, 1881

23. 'A Knight to Remember!' A talk by local Herefordshire historian and author, Barney Rolfe-Smith. Leintwardine History Society, November 20, 2022

24. ‘For the Love of Cider: Phenotyping Apples with Modern Techniques and Historic Texts', Biodiversity Heritage Library blog by Grace Costantino, June 2018 https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2018/06/for-the-love-of-cider.html

Comments