Miss Willmott's Daffodils

- gardenhistorygirl

- Mar 11, 2025

- 18 min read

'Narcissus Ellen Willmott', drawn in the Rev. G.H. Engleheart’s garden by H.G. Moon. From 'The Garden', July 31, 1897

The daffodil “is a flower we cannot do without”, from The Book of the Daffodil

by the Rev. S. Eugene Bourne, 1903

The daffodil can truly be said to be one of our most iconic, and much-loved, flowers. Its cheerful yellow blooms announcing the long-awaited arrival of spring and, for me, the beginning of my gardening year. According to the Royal Horticultural Society [see Note 1], today there are almost 27,000 daffodil cultivars, in a “dazzling array of shapes and sizes”, with the UK [and this rather surprised me] “growing more daffodil crops that any other country – about half the world’s total”.

An Announcement

And so, with the recent announcement [February 2025] from Plant Heritage and the RHS jointly asking the public for assistance “in finding rare and missing daffodils that risk being lost to history and science…” [see Note 2 ], Miss Willmott's daffodils seems to be an ideal subject for my March post. And if you need an introduction to my horticultural heroine, please see my other posts about her – although there's also a paragraph below giving some background. However, before I discuss Ellen Willmott's importance in the daffodil story, a brief introduction to the daffodil itself.

An Introduction to the Daffodil

The daffodil’s Latin name, Narcissus, has long been associated with the Greek myth of Narcissus who fell in love with his own reflection and who, unable to tear himself away, despite the exhortations of the nymph, Echo, died beside the pool from where, the story goes, the first Narcissus flower later sprung.

‘Echo and Narcissus’ by John William Waterhouse, 1903. Waterhouse’s version of the Greek myth illustrates the poem from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’. Public domain

Historically however, daffodils are said to have been cultivated for thousands of years by some of the world’s earliest civilizations, with wild daffodils first growing in Spain and Portugal before spreading across Europe. Although over the centuries they were usually used for medicinal and religious purposes, rather than ornamental.

As the RHS points out [in A Host of Golden Daffodils – The story of a springtime favourite (A history of one of our favourite springtime flowers through the collections of the RHS Lindley Library) see Note 1], the daffodil only became a popular ornamental garden plant in the Tudor and Elizabethan periods – somewhat surprising perhaps given that its appearance “was far less suited to the geometrical patterns and symmetry of the formal garden styles of the time”. It was John Parkinson, Apothecary to King James I, that championed the daffodil in his famous book, Paradisus Terrestris of 1629,“the first book in English concerned with the ornamental rather than medicinal uses of plants”, and in which he identified almost 100 different varieties of daffodil growing in England.

'Three daffodils, including the wild daffodil (Narcissus pseudo-narcissus): flowering stems with butterfly'. Etching by Nicolas Robert, c.1660. Wellcome Images under Creative Commons

However, between the late 1600s and early 1800s many of these old varieties fell out of fashion and were lost forever. The RHS further points out that the new rage of plant breeding in the early 1800s focused on exotic plants arriving from around the world, like orchids, and as there were large amounts of money to be made from such plants, there was little time for the humble daffodil.

Renaissance of the Daffodil

As daffodils are such a popular plant today, it’s difficult to believe that by the mid-Victorian period they had fallen out of favour. Yellow was considered an unfashionable colour at the time and gardeners, carried away perhaps by the constant arrival of those new and exciting plants, considered the daffodil too easy to grow.

Its renaissance was, according to the RHS, an altogether somewhat quieter affair, although the arrival of several new hybrids and pioneering ways of classifying them ultimately led to the “explosion of daffodil breeding” in the later 19th century. But, to begin with, the daffodil continued to be considered out of place in the Victorian formal garden until one Scottish nurseryman, Peter Barr (1826-1909), inspired by Parkinson’s long-lost varieties, began to build up his own daffodil collection. And his company, Barr & Sons, are credited with reviving the daffodil’s fortunes, finding new and forgotten varieties from around the world. As Barr himself wrote in 1870: “The Narcissus…is now reasserting its position, and claiming its proper place in the general economy of border decoration, and as a cut flower…” [quoted in the RHS's A Host of Golden Daffodils].

'The Gardeners’ Chronicle', March 15, 1884

An important event in this daffodil revival was the RHS's first Daffodil Conference held in April 1884. And it was Barr who persuaded the RHS to organise the conference, which was described as “a visually spectacular event held in a large conservatory at the Society’s South Kensington Gardens". The Conference led to the establishment of the RHS's Narcissus Committee, which oversaw “a new official classification framework for daffodils” – the RHS having responsibility, from this point on, to “name and register all new Narcissus hybrids”.

Illustration of Narcissi accompanying an article entitled ‘The Narcissus’ by F.W. Burbidge, Curator of Trinity College Botanical Gardens, Dublin. From ‘The Gardener’s Chronicle’, April 5, 1884

Another daffodil enthusiast, the Rev. S. Eugene Bourne, published The Book of the Daffodil in 1903, in which he wrote that, following Barr’s efforts, “there arose a band of daffodil enthusiasts such as the Rev. G.H. Engleheart and Miss Ellen Willmott...[amongst others] who, as cultivators, students, or collectors of wild forms and raisers of new seedlings, have rapidly enlarged and extended the knowledge and popularity of the plant... and the time seems fast approaching when everyone who has any pretensions to be a gardener will grow some at least of the finer varieties”.

And looking back to this time of the daffodil's revival as a popular plant, another RHS stalwart [who also regularly wrote for the horticultural press], the Rev. Joseph Jacob, wrote in The Garden of 4 May, 1916 somewhat dramatically, that “Miss Willmott was a good friend to the Daffodil in its early days when it was beginning to emerge from the darkness and twilight of the past, before it became the popular flower of today…".

Miss Ellen Willmott (1858-1934): a brief background

During the late 1800's until her death in 1934, Willmott was just as famous a gardener and well-known in the elite horticultural circles of the day as her friends and contemporaries, William Robinson (1838-1935) and Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932). And, like them, Willmott gardened in a more naturalistic way, using native plants and garden staples, as well as more exotic plants and new introductions. Willmott was also an accomplished photographer, and many of her photographs, including those of plants growing at Warley Place, were published in the horticultural press.

In 1894, Willmott (aged 35) joined the RHS – at this time membership being by invitation. She quickly became an established daffodil grower and hybridizer, winning numerous awards at RHS and other horticultural shows. Elected to the Narcissus Committee (the first lady gardener to join any RHS Committee) just 3 years later in 1897 – the two events, as her first biographer, Audrey Le Lievre wrote [see Note 3] being, by RHS standards, "an unusually, indeed an incredibly, short interval… ”.

Members of the Committee included daffodil specialists such as Engleheart, as well as nurserymen, including Peter Barr. Le Lievre points out that Willmott's fellow-Committee members were intrigued by her “enthusiasm, knowledge and intelligence” [after all she was a woman…!] and they gladly introduced her to other specialists.

Willmott spent a great deal of time and energy increasing the amount of daffodils growing in her gardens at Warley Place, and bought large quantities of daffodils from suppliers. She also spent some years raising various new hybrids, many of which were exhibited at RHS (and other) shows, while also growing on and showing new types she bought through a syndicate of buyers.

By around 1904, Willmott's garden at Warley Place was at the height of its fame. It became a recognised centre of garden innovation and excellence, and a constant exchange of seeds and plants took place between Warley Place, Kew, the RHS, and many other botanical institutions, nurserymen, horticulturists, plant-collectors and gardeners all around the world. And Willmott's horticultural activities, her plants, and her garden at Warley Place, regularly graced the pages of the horticultural press.

'Warley Place'. Watercolour by Alfred Parsons, c.1906. Creative Commons

Between the years 1900 to 1906, the height of her daffodil activities, Willmott took a “formidable" number of Awards of Merit for daffodils of various classes, as well as being awarded an RHS Gold Medal for “various groups of fine and rare daffodils”. Willmott was highly respected in the horticultural world, and often thought “unrivalled as a cultivator of difficult subjects, searching out their requirements with patience and care" – truly a great, and successful, proponent of what we'd now call ‘right plant, right place’. [Quotes from Le Lievre's biography.]

One of the highlights probably being her award of the Peter Barr Memorial Cup in 1918. The Gardeners’ Chronicle of April 27, 1918 reporting that the Cup was awarded to Willmott “as an acknowledgement of the good work this lady has done in popularising Daffodils”.

Miss Willmott's Daffodils at Warley Place

The main famous flower gardens at Warley Place were surrounded by park-like meadows planted with clumps of coniferous and other trees, under-planted with grouped masses of snowdrops, crocus and daffodils. It's thought that some 600 varieties of narcissus were planted at Warley Place, with Willmott planting not just daffodils, but snowdrops, fritillaries, camassias, tulips and muscari by the thousands – all planted in naturalised groups.

'Warley Place'. Watercolour by Alfred Parsons, c.1906. Creative Commons

Willmott’s own photograph of the old walnut tree standing in the meadow in front of the house surrounded by narcissi, published in The Garden in 1897 (see below), perfectly illustrated the new trend of planting daffodils and other spring bulbs en masse, and arranged in groups or drifts. However, as all Willmott's published photographs are black and while, it takes an artist to give us some idea of what a wonderful sight her daffodils must have been. Fortunately, the artist Alfred Parsons (1847-1920) painted several views of Willmott's home and gardens (as can be seen above) c. 1906, all just titled 'Warley Place'. And his colourful paintings show the glowing yellows and whites of the many daffodil species growing in the meadows and surrounding the house.

Article titled 'Narcissus in the Grass at Warley Place' in 'The Garden', March 6, 1897, accompanied by Miss Willmott’s photograph, ‘Narcissus time at Warley Place’

Growing Daffodils in grass

Today, Warley Place (now a nature reserve run by the Essex Wildlife Trust) is still well known for its displays of daffodils during the spring, and special open days at the garden draw hundreds of visitors. And yet, back in the late 1800’s, growing daffodils and other spring-flowering bulbs in grass in gardens was quite a new concept – and very much part of the emerging ideas about gardening in a more natural way as espoused most famously by William Robinson and his ideas about the 'wild garden', as well as by Willmott and Gertrude Jekyll.

Robinson and Willmott in particular became well known for planting daffodils amongst grass, and were mentioned in an article written by F.W. Burbidge in 1905 titled 'Daffodils in Meadow and Lawns'. Burbidge writing that “outside of Nature’s own perfect way”, the best “object lessons on artistic planting of bulbs in grass” was at Willmott’s Warley Place and Robinson’s home, Gravetye Manor. Such spring-planting became increasingly popular, and the term ‘naturalising’, in relation to spring bulbs, "entered garden jargon" [see Note 4].

'Daffodils in the Birch Grove at Warley Place'. Photograph by Reginald Malby from 'Country Life', 8 May, 1915. This photograph accompanied an article about Warley Place by 'Country Life’s' editor, H. Avray Tipping

So how wonderful that, over 100 years later, one of the UK’s largest gardening websites, Crocus.co.uk's, advice for naturalising narcissus (or crocus) bulbs in grass in order to achieve a more natural look is [as noted in her first biography] to "copy the famous Miss Ellen Willmott of Warley Place in Essex”, who “placed a small child in a wheelbarrow with a sack of bulbs and pushed it along whilst they showered the ground with bulbs”. However, I doubt very much that Willmott did any pushing herself – it would have been one of her many gardeners, or at least a footman!

Robinson himself was complimentary about the drifts of daffodils growing at Warley, writing in The Garden in 1909 of “the glorious carpets of colour” they made. While Jekyll wrote, in Country Life in 1910, that Warley Place had “oceans of many kinds of Daffodil". The photograph below showing such drifts beautifully.

'Narcissus drifts and shrubs at Warley Place'. Photograph by Reginald Malby in 'Country Life', 8 May, 1915.

Warley Place today at Daffodil time. Photo by author

Engelheart also described the daffodil planting at Warley Place in The Garden, 20 January, 1900: “…seen on a showery spring morning, under broken light, their massed clusters of bloom have an unrivalled quality of glistening pearliness, while their fragrance is delightful in the open air…”. He also describes “a Daffodil dell…consecrated to a noble collection of the finer kinds, planted informally in clumps and in small beds of varying size and form cut out of the natural turf… in nooks… and other spots are Daffodils of still greater rarity and beauty, many of them not to be found elsewhere”.

Sadly, most of the more interesting daffodils are long gone although Warley Place today is still a wonderful sight at daffodil time and well worth a visit, particularly in the spring – as the photograph below shows, courtesy of one of Warley Place's hard-working and knowledgeable volunteers.

Photograph of Warley Place in spring by Fiona Tittensor

Miss Willmott's award-winning Daffodils

As already mentioned, Willmott not only grew many different kinds of daffodil at Warley Place, but also hybridised them herself, and showed them regularly at RHS shows and Narcissus Committee meetings. The Rev. Jacob described [in this article in The Garden of 4 May, 1916] how "keen she and her sister Mrs Berkeley were 15 or 20 years ago. What delightful exhibits they staged in London and Birmingham. Miss Willmott was almost the first, if not the very first, amateur to get a gold medal for a group …" [at an RHS show].

The gold medal Jacob refers to was awarded to Willmott at the Narcissus Committee meeting held on 3 May, 1904 “for a group of Daffodils remarkable for the fine development of the flowers and containing the newest varieties… Having regard to the beauty and rarity of the Daffodils, no finer group has ever previously come before the Committee”.

There are many articles as well as reports on prizes and awards to Miss Willmott for daffodils – too many to detail here. However, Miss Fanny Currey, an Irish plant breeder and nurserywoman [and another fascinating, feisty Victorian woman worthy of a post in the future!], writing in William Robinson’s short- lived journal, Flora and Sylva, in April 1903, probably sums it up nicely [see Note 5].

“Any notice of new Daffodils would be very incomplete if it contained no mention of the many fine exhibition Daffodils, as well as interesting and rare forms of the flower, shown from time to time on the Narcissus Committee table in London and at the Birmingham shows by Miss Willmott, whose collections at Warley simply embody the whole history and science of the flower. Among her important contributions during the last couple of years may be named Earl Grey, Countess Grey, Robert Berkeley, Charles Wolley-Dod, Betty Berkeley, Warley Magna, Incognita, and those brilliant flowers, Oriflamme and Cresset”.

And here, just a brief note about the "Birmingham shows" mentioned above. During this period, the Midland Daffodil Society's shows, held at the Birmingham Botanic Gardens, were just a big a deal as those of the RHS, and attracted Willmott and others of the horticultural elite, who exhibited at them regularly. And a report on one of the Society's shows, published in The Garden in May 1900, gives me the opportunity to highlight the often delightfully outmoded language of the time used in some of these articles. [At my age a major 'eye-roll' is sufficient…!]

“Every year the lovers and growers of the Daffodil flock more and more to... Birmingham [then lists some male exhibitors]… Last, but by no means least, on this occasion were the ladies, who gave their gentle and bright allegiance to the Narcissus…, Miss Ellen Willmott of Great Warley, Mrs Backhouse, Miss F.W. Currey of Lismore… were only a few who graced the exhibition by their presence…”. [see Note 6].

List of Awards presented at the 6th Annual exhibition of the Midland Daffodil Society in April, 1904. From 'The Garden', 30 April, 1904

Daffodils named for Miss Willmott or Warley Place

There are also several daffodils named for Willmott herself or Warley Place: Ellen Willmott; Great Warley; Warley Magna; and Warley Scarlet – all produced by the Rev. Engleheart (1851-1936). He was amongst the first great amateur daffodil breeders, producing hundreds of named varieties, many of which received awards from the RHS. His work in this area was so prolific he was nicknamed the ‘Daffodil maker’ and ‘the Father of the Daffodil’.

Plate 4, depicting no. 17, Narcissus Ellen Willmott. From ‘Beautiful Bulbous Plants for the Open Air’ by John Weathers, 1911

The others are N. Miss Willmott, produced by Dutch nurseryman, botanist and hybridiser, C.G. van Tubergen (1844-1919); Willmott's own hybrid, N. Warleyensis; and N. Orange Warley from L. Buckland, this being, apparently, a N. Great Warley hybrid.

In March 1897, N. Ellen Willmott, raised and shown by Engleheart, won an RHS first class certificate – The Garden describing it as “being perhaps so far the very finest of all seedlings raised in England or elsewhere…”. The accompanying article pointing out that it was named “in compliment to Miss Ellen Willmott, of Warley Place, a most enthusiastic and successful amateur gardener”.

An example of Willmott's activities at the Narcissus Committee comes from The Garden, where she exhibited a small stand of flowers at their meeting of 7 May, 1904. Described as being “one of the chief centres of attraction… all the varieties of high merit… splendidly grown and most tastefully arranged”. They included N. Great Warley, which received a first-class Certificate – E. A. Bowles had Great Warley growing in his garden, writing in his book My Garden in Spring, 1915, that he considered it one of his “newer, choicer treasures…”, while N. Warley Scarlet was described by the RHS as “so far the finest of all the [Engleheart hybrids] and probably the loveliest flower which has been put before the Committee this season”. Warley Scarlet can be seen in the illustration below.

Report of the meeting of the RHS Narcissus Committee held on 19 April, 1904. From 'The Garden', 7 May, 1904

‘Some of the Newer Narcissi’ – this illustration features N. Warley Scarlet. From ‘Supplement to The Garden’, August 14th, 1909

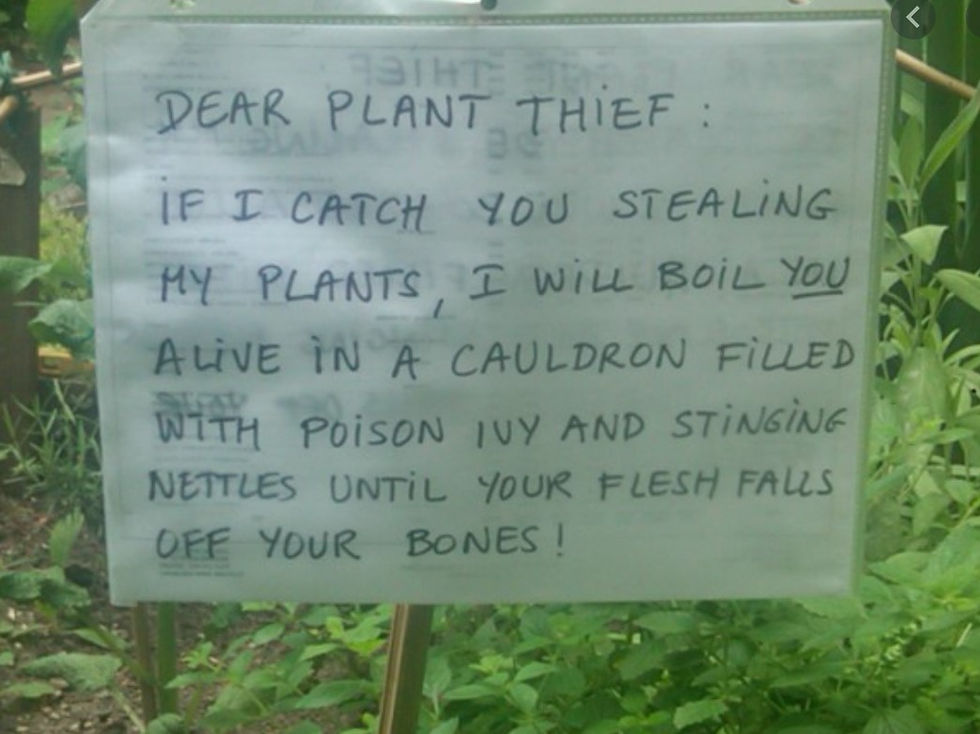

Willmott's booby-trapped daffodils

I can't write this post without mentioning Willmott's booby-trapped daffodils at Warley Place. It's one of the most often repeated stories about Willmott, and generally used to illustrate her increasing eccentricities as she aged. In addition to employing a night watchman, it's said she instructed her Head of Gardens to booby-trap her precious daffodils by fixing tripwires in the meadows where they grew. These wires would “set off air guns and frighten the life out of anyone hoping to pick a bunch surreptitiously”[ see Note 3], as well as alerting the watchman.

Although often considered as just a ‘story’ – or at best an exaggeration, I found a first-hand account of these elaborate precautions in an article published in the Gardeners’ Chronicle of America in May 1922 by Montague Free, a gardener who had worked at Warley Place between 1906 and 1908 [see Note 7]. After his time at Warley, Free worked at Kew for several years before emigrating to the US where he rose through the gardening ranks to become Head Gardener at the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens in New York, as well as a notable garden writer.

Written in praise of flowering spring bulbs grown in grass, Free's article mentions the theft and vandalism that he encountered regularly at the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. While public gardens often suffered such problems, he acknowledged that "flowering material" in private gardens was “not always immune”. And goes on to describe Willmott's practice of hedging the flowers around with trip wires attached to a loaded gun during their blooming season. As he pointed out, the bulb fields at Warley Place could be seen from a public road and, as London was not too far away, “it would be quite easy for persons from the wicked metropolis to come out in autos, load up with flowers, and dispose of them in Covent Garden market.” So perhaps Willmott wasn’t as paranoid as some writers seem to think!

‘Narcissus poeticus Seagull at Warley. From photograph by Miss Willmott’. From ‘Gardening Illustrated’, 23 March, 1901. Seagull is an Engleheart hybrid, still available today

In fact, Willmott had good reason to be cautious about her plants. In April 1931, a short article in a local paper, The Chelmsford Chronicle, reported that two young men were summoned to the local magistrates court for stealing a quantity of daffodils, valued at 4 shillings, from Warley Place. Caught with armfuls of daffodils by a local police constable, they admitted taking them from one of the meadows. However, it was agreed they had committed the offence in ignorance, although the Chairman of the court warned that “it was a great nuisance that the flowers which decorated the countryside should be torn up by hordes of people.”

The magistrate seems to have missed the point though, that these daffodils would have been planted by Willmott and her army of gardeners, and some of the narcissus growing in her meadows would have been specialised or new varieties – which took a considerable amount of time and work to produce, rather than the more common ones.

U.S. connections

Continuing on the theme of the U.S., Willmott's daffodils also made it across the 'pond'. In the U.S., horticultural organisations such as the Garden Club of America and the Massachusetts Horticultural Society reigned supreme, and had connections with the UK.

A leading member of the Garden Club of America, Louisa Boyd Yeomans (1863-1948), called by some the “fairy godmother of gardening in America”, was also an author, writing under the name Mrs Francis King. In one of her books, Pages from a Garden Note-book, published in 1921, she writes of her English daffodils:

"I came in from the garden with my small copper watering can… filled with choice labelled daffodils, every one new to me this year. Of these most have graced tables in English shows for some years past, and some American amateurs have had them in their gardens for almost as long; but these of mine were bought lately, and it is an excitement of some intensity to watch the varieties as they open. Tresserve is a glorious clear yellow trumpet of great size… Great Warley [and] Miss Willmott…are very fine”. [Tresserve was produced by a Dutch nursery and in all likelihood named for Willmott's garden in France, although I've not found any written evidence of this.]

King also writes of meeting Willmott in London on two occasions in an article, ‘Pleasures of Gardening’, published in The National Horticultural Magazine [the Journal of the American Horticultural Society], January 1941, where she describes Willmott as "a great botanist [who] became known the world over". Although neither the date the article was written, nor the date of her meetings with Willmott are given.

I slightly digress even further here, but Willmott's connection to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society is interesting as it provides yet more evidence of her standing in the horticultural scene of the day. ‘MassHort’, as its usually known, was founded in 1829 and is the oldest, formally organised horticultural institution in the US. The Society allowed ‘corresponding members’ – those from the U.S. “or any other country, distinguished for their practical skill and knowledge in the science of horticulture” [see Note 8]. Willmott became a corresponding member in 1906. Other U.K. members of note were William Robinson, the Secretary of the RHS, plant-hunters Ernest Wilson and Augustine Henry, famed nurseryman Harry Veitch, and directors/curators/officers of various botanic gardens, including those from Kew, Edinburgh and Dublin.

Miss Willmott moves on...

I hope this post shows that Willmott was indeed an important player in the story of the daffodil's revival, and the "explosion of daffodil breeding” towards the end of the 19th century. By the early years of the new century however, many of the successful daffodils Willmott had been showing had passed into trade, and she gradually ceased to exhibit them at RHS shows – although she continued as a member of the Narcissus Committee.

'N. Pseudo-Narcissus var. Cernuus', Plate 8 from 'The Narcissus; Its history and culture' by F. W. Burbidge, 1875

She also continued to attend RHS meetings, and was well known for sporting unusual flowers on her dress – the Rev Joseph Jacob, in his book, Daffodils, published in 1910, commenting "that few could grow the lovely N. Cernuus plenus [the wild, 'Old Double White Trumpet Daffodil'], although Miss Willmott, in her Essex garden, can grow it well and she has frequently been seen at the spring shows with a grand spray of it on her dress”..

Willmott moved on from hybridising daffodils as her focus of attention turned to the flood of new, exciting bulbs and seeds from China, collected by the likes of plant-hunter, Ernest “Chinese” Wilson – exhibiting many at RHS shows, but that’s another story, and another post!

Postscript

Narcissus 'Great Warley' from Croft16daffodils.co.uk

Many of the daffodils grown or shown by Willmott are still available, although those named for her or Warley Place are mostly not – and therefore presumed lost.

However, I've seen N. Great Warley for sale from a Scottish online daffodil supplier, as of 2024 [see Note 9], although I believe Spetchley Park in Worcestershire has Great Warley growing in its gardens [Spetchley being the home of the Berkeley family, into which Willmott's sister, Rose, married]. Back in 2011, I also found a photograph of Warley Magna on the US Daffseek website, but this year it's no longer there.

Narcissus 'Warley Magna' from daffseek.org

Of course many of these daffodils, and others, may be happily growing in gardens and parks unnamed and unknown. The main reason, of course, for the Plant Heritage and RHS initiative.

Further reading:

Most recent, and excellent, biography of Willmott by Sandra Lawrence: Miss Willmott’s Ghosts: The Extraordinary Life and Gardens of a Forgotten Genius. Sandra also posts regularly about Willmott at misswillmottsghosts.com and also see her A Year at Warley Place, Part IV: Daffodils – The Event Gardener

Notes:

1. A Host of Golden Daffodils – The story of a springtime favourite (A history of one of our favourite springtime flowers through the collections of the RHS Lindley Library) RHS Lindley Library – Digital collections / RHS ]

2. Plant Heritage. Announcement of 12 February, 2025 “Join the ‘Hunt for rare daffodils’ that are slipping from history”

3. Audrey Le Lievre, Miss Willmott of Warley Place, Her Life and Her Gardens, 1980

4. Kay N. Sanecki, ‘The Craze of Many’, Garden History, Vol.24, No.1 (Summer,1996)

5. Extract from article 'New and Beautiful Daffodils', by F.W. Currey, Lismore. From Flora and Sylva, Vol.1, No.1, April 1903

6. The Mrs Backhouse mentioned here is the lady for whom N. Mrs R.O. Backhouse is named – the daffodil that Plant Heritage are so keen to find. An established daffodil breeder herself before marrying into the famed Backhouse nursery family, it was her husband who named his new daffodil after her death.

7. Article: 'Things and Thoughts of the Garden', by Montague Free. From Gardeners’ Chronicle of America, Vol.24, No.5, May 1922. Also see my post Booby-trapped daffodils and a stolen water lily: 100 years of plant thefts from 2021.

8. Article 26, ‘Who may be Corresponding Members’, from Proceedings on the Establishment of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1829. U.S. Library of Congress.

Willmott's membership is noted in their list of Corresponding Members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, (as of) 1923. Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society

9. Croft16Daffodils at a cost of £3.50 (presumably per bulb).

Images from Country Life from

Just been planting lent Lilly. A bit late due to situation at home but hope they will appear next year.

Wow! But what can one with a small border do? How to decide which bulb to buy? Thanks for the blog.😍

Wonderful stuff, Paula! I am now convinced that Ellen did boobytrap her daffodils, as the air guns and, if memory serves, the trip wires were included in the 1935 sale.